"Deep breath in," the delivery nurse said. "And push on the way out as I count... 1, 2, 3..."

"Let's go, Amanda. Dig deeper," I said, holding Amanda's right leg.

"4, 5, 6..."

"You can do this. Let's see a big push," Amanda's mom said, holding the left leg.

"7, 8, 9..."

"Dig deeper," I say again. "This is worth all the shots and all the time we've waited."

"One more big push... 10. Relax," the nurse said to close the round.

Those were the words repeated in various forms for the 59 minutes it took for Amanda to push Eliza out into the world and the bright fluorescent lights of the delivery room at St. Joseph Hospital in Tacoma.

Her stats: 8 pounds, 11 ounces. 21-inches long and a full head of black hair. 100-percent perfect.

We had waited a long time for this moment. Four years since we started trying, two years of fertility treatments. Three lost embryos earlier in the year, including one transferred with Eliza. But she made it, and she was healthy.

Like our journey to become parents, Eliza's birth didn't go as we had planned.

On Friday, October 9 at 2 p.m., Amanda's water broke while she was napping at home. I was working upstairs and Amanda's parents, Roger and Sheree, were on watch. Sheree hollered up the stairs to me, "Amanda's had a spontaneous rupture of membranes!" which is nurse-speak for Amanda's water breaking. All nurses I've met like to speak in technical terms to medical laymen.

I ran downstairs to confirm the news. Amanda was already in the shower. I immediately started repacking, which was totally unnecessary because a) we were packed just fine and b) labor takes a long time. I knew that, but I wanted to feel like I was doing something productive. Amanda called the nurses at the hospital who told us to come in at 2 a.m. if active labor didn't start earlier.

For the next several hours, we passed the time impatiently like 7-year-olds on Christmas Eve but coped like adults: We cleaned the house. We went for a walk. We ate dinner. Amanda baked some knock-off (but better) Starbucks pumpkin bread. I tried renting the new Avengers movie but the streaming kept stalling. It felt like forever.

Not much was happening, so we went to bed with alarms set for 1:15 a.m., or about two hours later.

We woke up from our nap and set off for the hospital on that early Saturday morning. We had to check-in at the emergency room, per protocol, and briefly witnessed the type of folks who hang out at the emergency room at that time of day -- a few with real issues, a few looking for a prescription medicine fix.

In short time we were wheeled off to our first of many rooms, which I'll call the "Not Sure Room." It's the room where a lot of women go if they're not sure they're in labor yet. Many are sent back home. In our case, we weren't sure that Amanda's water broke or if she peed herself (it's common for pregnant women to occasionally lose bladder control based upon where the baby sits).

Amanda took a test and we got confirmation that Amanda's water had in fact broke, and the baby needed to come out within the next 12 hours or so to prevent chances of infection. We walked across the floor to our second room, the "Labor Room."

The irony of being in the Labor Room was that there still wasn't much labor happening. At 4 a.m. I crashed on the cot in the room to sleep. We sent Roger home, and Sheree stayed on watch through the early morning.

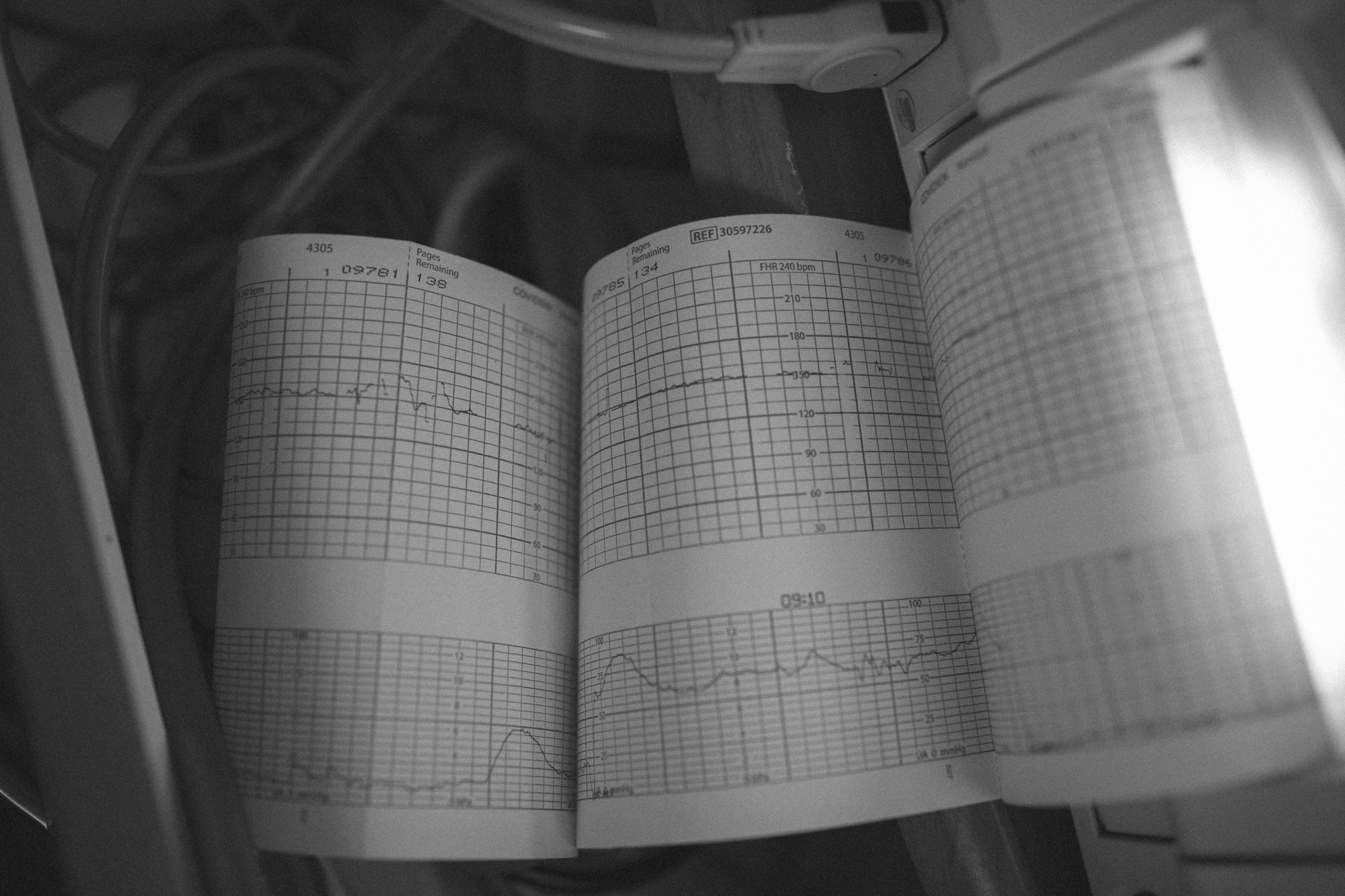

In the late morning there still wasn't much happening. At 7:30 a.m. the nurses started Amanda on a pill to try and get things started. No luck. At 9 a.m. they started her on a low dose of pitocin, or "The Pit," to induce labor. We weren't thrilled to start pitocin after learning in labor class how it intensifies labor, but we didn't have a choice.

We sent Sheree home to rest. Amanda and I got bored waiting for contractions to pick up. We ran out of things to talk about. The nurses came in and out of the room every 30 minutes to crank up the pit dosage and warned Amanda of a long labor ahead.

At 1 p.m., nearly one day after her water broke, Amanda finally started active labor. The Pit lived up to its reputation. Labor hit Amanda like a wrecking ball. She went from a relaxed state to intense contractions that she took leaning over the side of the hospital bed. We talked through her breathing exercises, which helped me too as I slightly panicked watching my wife handle the worst pain of her life.

Amanda asked for some relief and the nurses put something in her IV that made her nauseous. Soon she was leaning over a puke bag during contractions. I called Sheree to have her come back to the hospital. We needed back-up. Amanda asked for an epidural and a light at the end of the labor tunnel.

Sheree arrived and helped us get through this phase of labor. Whereas I felt increasingly helpless as the contractions got increasingly intense, Sheree locked eyes with Amanda and coached her to focus. It was a true mother-daughter connection. Amanda dilated from 1 centimeters to 7 centimeters in three hours, and we were moved to the Delivery Room. Amanda had done a lot of hard work by the time she got the epidural at 4 p.m. She got the relief she was looking for and rested a couple hours.

By this time I got hungry for dinner and walked across the street from the hospital with Roger to Ezell's for some fried chicken. I told the cashier we were having a baby in the next few hours and scored a free slice of peach cobbler. That put a skip in my step.

I slammed the food with Roger and Sheree in the Waiting Room and went back to the Delivery Room. Amanda was getting prepped to push and we started the real work with Sheree alongside just before 6 p.m.

The nurse told Sheree and I to each grab a leg and gave Amanda a crash course in pushing with an epidural. It's a lot of effort without a lot of sensation.

"Deep breath in," the delivery nurse said. "And push on the way out... 1, 2, 3..."

After 30 minutes of pushing, Amanda developed a fever and the baby's heart rate had shot up -- neither were good signs. It created an urgency to get the baby born soon to avoid a c-section. We saw meconium (baby poop) start to come out with the pushes, which was also a sign that the baby was in distress. I think that knowledge drove Amanda that much harder.

At this point, I'll pause and say that Amanda was so impressive through this experience. Words cannot express how appreciative and humbled I am by her perseverance through this day, the entire pregnancy and infertility treatment. I am so proud of my wife.

Witnessing a birth is one of the most incredible experiences and life-changing. I have a new appreciation for women and what their bodies are designed to do. Before having a child, a lot of people talk about "looking south of the equator." Well, my friends, I say put that trip on your bucket list. You don't get to see a miracle every day.

I started to get emotional when the head was cresting. It's probably strange to read that but you have to understand that I was seeing a part of my child for the first time. I saw the cowlick on the back of her head and it was like mine. After that point, it only took a couple more big pushes until the head was born and another push for the shoulders and the rest of her body.

Eliza was Barney-purple when she came into the world with a cry at 6:51 p.m. on October 10. I matched that with a hard cry of my own. She was placed on Amanda's chest and the nurses roughed her up a bit to help her adjust to the outside world. I grabbed my camera and took photos. Eliza made her instinctual breast crawl and latched for the first time. I cut the cord with a single snip. Sheree took a few photos for us. It all happened so fast over the course of Eliza's first hour of life.

Eliza was born on a dark and stormy night.

It's as fun to type that as it is true. The views on the 14th floor of St. Joseph's Hospital are excellent, but we could hardly see a few feet outside the window that night. The rain blew sideways and flooded Stadium Bowl. It was all so intense and appropriate to me. If getting married on a rainy day is good luck, then being born in a northwest monsoon must be a blessing.

We felt relieved, we felt blessed. Our prayers were answered.

I can finally say, happy birthday, Eliza.